This is one in a series of posts on the challenges of ebooks. Conversation about the topic is hosted by the Books in 2025 group. See the discussion topic there.

opinion by Tim

A recent blog post at Dear Author raised the issue of ebooks and ownership rights. Ebooks are redefining ownership toward access rights. New models are emerging, like advertisements in books. Jane concludes:

“I’m sure that there are other possibilities but with the amelioration of ownership and comparable media prices, digital books will come down from their current position and this, in turn, will create new business models and new pricing models. Could publishers resist the downward pressure of ebook pricing by coming up with a business model which would result in increased sense of ownership and thus value to the consumer? Is cloud access that model? What other ways could publishers and authors increase the value of ebooks to consumers?”

I suspect the answer is nothing. The loss of ownership creates a downward spiral in value, and erodes the very notion of paying for books at all.

Defining ownership down. We used to own our books. With most ebooks we own them in name, but effectively we lease them. As Jane documents, the slide toward more and more attenuated concepts of ownership continues.

The process is gradual. Mental models change slower than technology. If the Kindle had debuted with an access-based “faucet” model, it would have failed. Consumers would not have traded true ownership for a tethered, metered and monitored product. But we’ll get there soon enough, as each step away from ownership makes the next step more acceptable. Once you realize your Kindle book is not fully yours, you’ll accept it being mostly not yours. Google Ebooks are a further step away from ownership. Eventually you get to a faucet model, as music has done, either low-price (Netflix) or free (Pandora, YouTube).

By itself, such changes might be culturally and economically neutral. Ownership of paper books wasn’t so much a consumer preference as a side effect of their physical nature, and law followed and solemnized that state of affairs. Maybe the faucet model will produce more readers, more reading, more good books, more paid authors, etc. Or maybe it will produce less. Who knows?

The role of piracy. I think we know. And the trends are negative, for both readers and authors.

Unfortunately, digitization and the faucet model tends to encourage a third option–piracy. Digitization makes it possible, but the faucet model encourages it. This happens in two ways.

First, people who love autonomy and personal freedom rebel against metered and monitored access to reading. They don’t want inconvenient DRM, monstrous and opaque licenses, transfer limitations, constant access requirements or icky, opaque monitoring. These people will turn to piracy to avoid it. (Or at least that’s what they’ll say they’re doing.)

Second, the more ownership is devalued, the less people care about the rights of the seller. When someone sells you something they made, or through a small number of simple intermediaries, it’s easy to see what’s wrong about cheating them. When authors’ work is reduced to a limitless soup, available through shiny digital spigots at cheap, but limited, rates, it’s hard to see where problem with piracy really lies, and easier to rationalize cheating authors.

As devalued ownership feeds piracy, rising piracy in turn devalues ownership. Anyone with an internet connection can rapidly assemble a “library” of books it would have once taken years to build–so why bother building one?

As the logic churns, content sellers will increasingly seek other ways of “monetizing.” Authors will charge for readings, or merchandise. They’ll try advertisements. They’ll start leveraging all the user data they’re collecting to create even better ads. None of this will replace more than a fraction of the book economy, but they will definitely send a message to consumers: You’re being screwed enough to pay for the privilege.

Look elsewhere. Does impaired, devalued digital access encourage piracy? Many ebook pundits dismiss ebook piracy. “New models” will emerge. Piracy is better than obscurity. People will pay once everything is available for a “fair” price. The arguments are familiar, and have an air of ritual now. Hip conferences urge publishers to do a swan dive into an empty swimming pool.

Don’t need to take my word for it. Just look at all the other industries that have gone digital. Take music. Physical music sales have been declining steadily for more than a decade, and while digital sales rise, they make up only a fraction of the loss. (They’re not even rising much anymore either.) Revenue from Pandora, Spotify, YouTube ads and the like are loose change next to CD sales declines.

What’s the shortfall? All told, the United States recorded music industry is worth less than half of what it was a decade ago, and the downward slope is only getting steeper. Outside of the big markets, the declines are greater. The Spanish music industry fell 55% in the last five years alone. In China rampant CD copying and file sharing have left a nation of 1.3 billion people with a $75 million recorded-music industry. As a recent Economist report put it, the “worst-case scenario has already come to pass.”

Music has it easy compared to writing. Musicians have always relied on other revenue sources. Performance is the big one, but merchandise and licensing matter too. Authors don’t have the same options. Dickens engineered a profitable reading tour of the United States, as new-model enthusiasts always point out. But how many authors could do that today? How many could fund themselves on t-shirt sales. And will anyone pay authors to read sentences from their novels over an Audi advertisement? The ringtone market holds limited prospects.

The unashamed future. As William Gibson said, “The future is already here; it’s just not very evenly distributed.” I saw that future at a recent technology conference, hosted by NYU. Of course, the participants were all well down the digital road. All read digital books, and many had given up paper entirely. (In certain circles announcing that you haven’t read a physical book in X months is a boast, and people compete to have the highest number.)

But one individual stood out. In a mixed crowd of peers and professors this brave futurist shared her decision to stop buying book altogether. She loved books. She read a lot. But she could find everything she wanted to read on BitTorrent. Nobody objected. It may have been my imagination, but I thought I saw a mystical crown settle squarely on her head. She was the coolest person in the room. She was the future.

Publishers and authors, meet that future. And know that with every move away from ownership you are hastening its arrival.

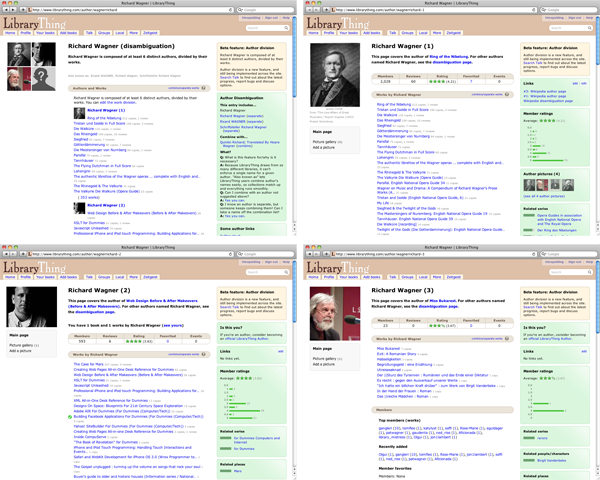

choose just one title from a list of all the books by that author (this step is useful in making sure we have the right one in case of split authors), and then we’ll confirm Author status.

choose just one title from a list of all the books by that author (this step is useful in making sure we have the right one in case of split authors), and then we’ll confirm Author status.